February 28, 2019

by ISB Native Language Programs

1 Comment

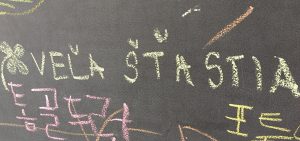

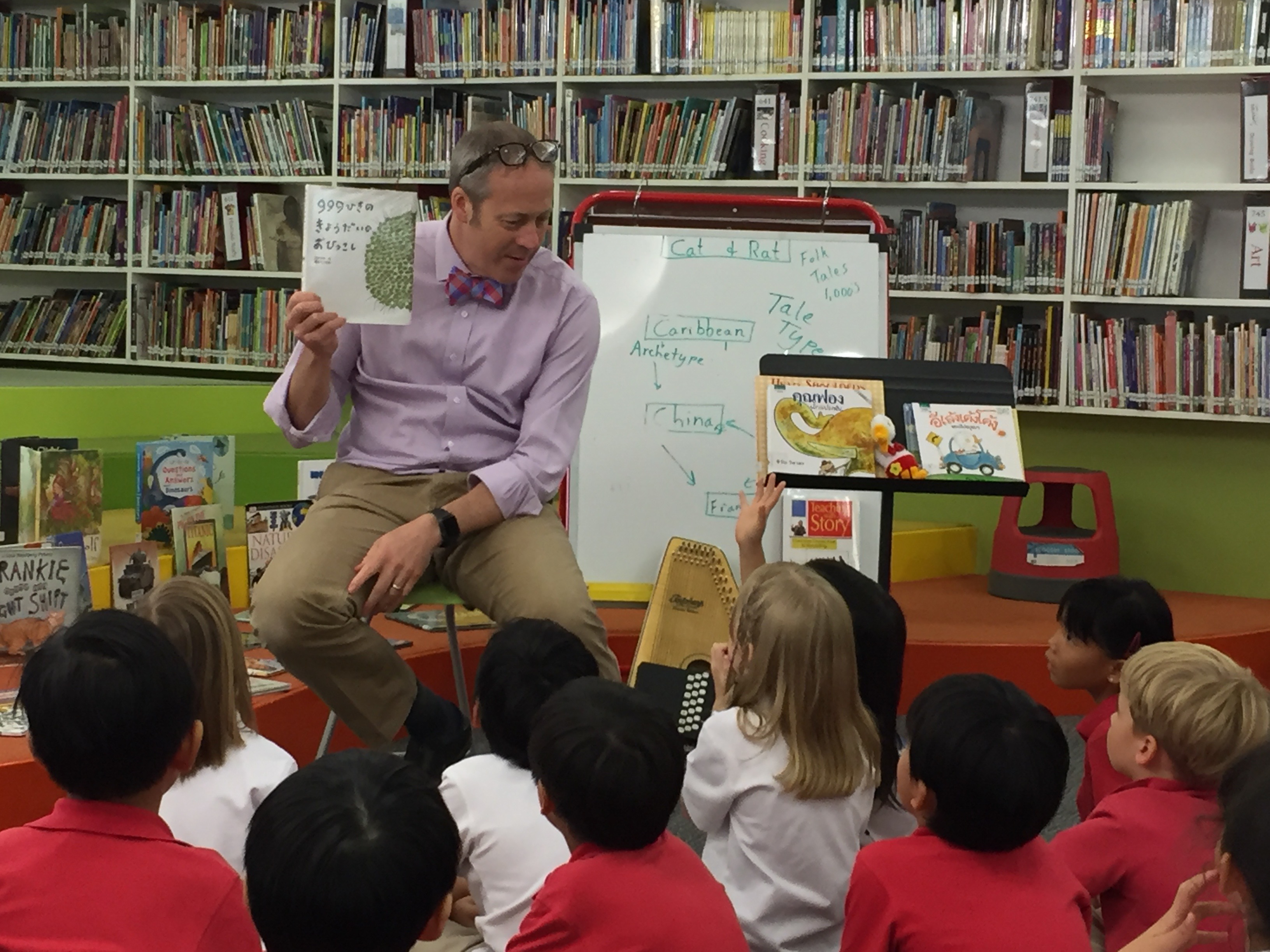

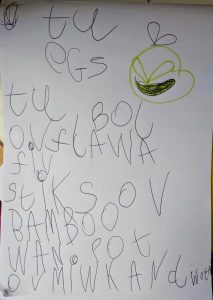

A moment of precious time with our grandchildren: pencils and paper, puzzles and activity books, scissors and glue are scattered about the table. Michelle draws an object of her imagination: a special vacuum cleaner. She draws arrows and labels different parts of the device. Then she gives her drawing a title. She admires her work—the writing is a mix of Cyrillic and Latin scripts. She sometimes finds it easier to write words in the Russian Cyrillic alphabet, with its near-perfect letter-sound correspondence.

Drawing labeled in both Cyrillic and Latin scripts.

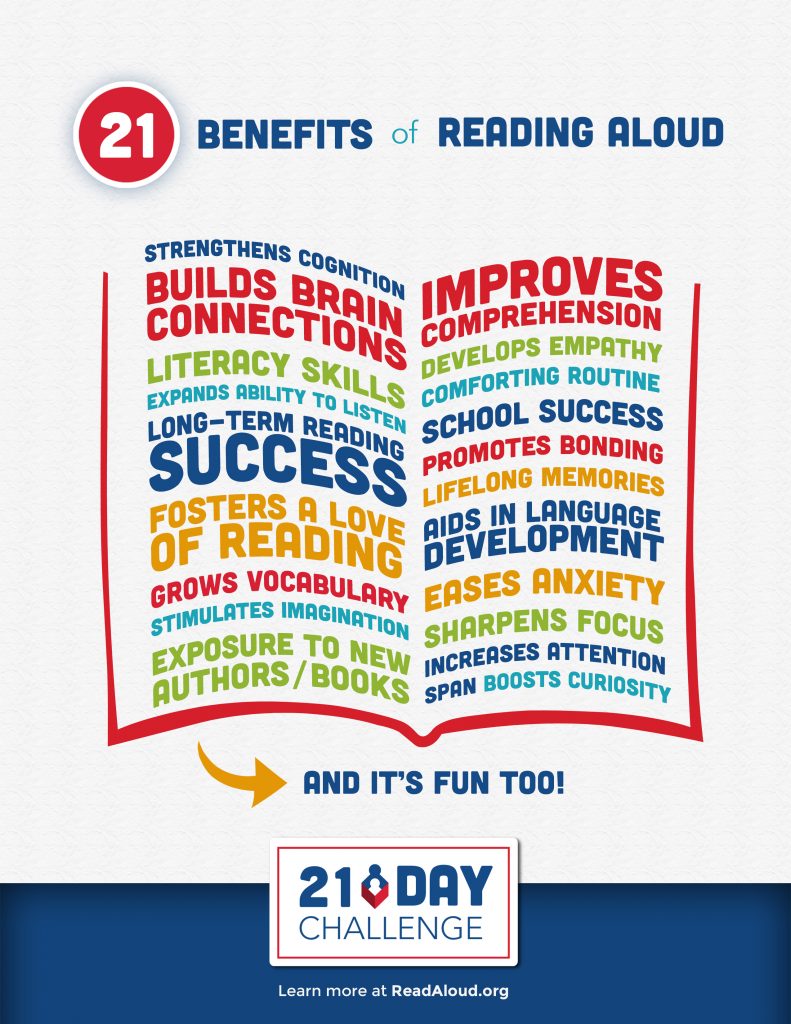

Michelle is taking her first steps toward literacy. We tried hard to prepare her for these moments. She has been read to extensively, and she has been learning letters through various games and activities. She knows letters in three languages: Russian, French and English. She is beginning to read simple books in English at school and to write phonetically.

We have anticipated this stage, and now it’s exciting to watch how engaged and focused she is.

Along with excitement come worries.

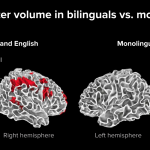

Languages are written in different ways, sometimes with no similarities at all, and sometimes with similarities that confuse. Children must figure out how letters and signs of different scripts work together to form words and sentences in each language.

Should we encourage Michelle to read and write in all three languages at the same time? Should we wait and let her develop skills in the language of her educational setting, which is English, before attempting to introduce literacy skills in French and Russian?

Many parents have to answer these questions and address these worries. Research on this matter is not prescriptive; it does not supply a clear recommendation or a timeline for learning multiple literacies. What it does say, is that learning to read and write in one language will make it easier to learn to read and write in another, as many reading and writing skills are universal. Research also cautions against disregard for the child’s interest and motivation. Frustration in learning to read and write, which some children experience, might signal some general difficulties in learning, rather than the effect of multilingualism.

On the positive side, the simultaneous approach has great potential for broadening the learner’s perspective on literacy, making comparisons, analyzing more deeply the structural elements of each language, and understanding the purposes and cultural aspects of reading and writing.

Indeed, literacy in several languages can be the key to vast linguistic and cultural resources and the foundation of globally-minded learning. It gives access to diverse knowledge and worldviews.

Two months after labeling her vacuum cleaner, Michelle reads a book in English that she has brought home from school. She is “sounding out” letters and reading simple words on a page. Then she has an idea. “Mama, I will now read this book in Russian,” she says. “I will read the words quietly in my head, in English, and then say them in Russian.” And she does.

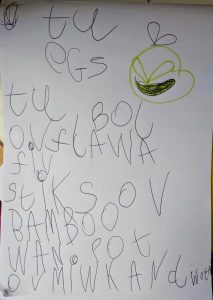

Another day, Michelle creates a text, a recipe for her panda’s favorite soup. She announces the purpose of her writing clearly, in Russian, and then begins to write in English, saying the words slowly but recording with amazing fluency.

Soup for a panda. Ingredients: two eggs, two bowls of flour, five sticks of bamboo, and one pot of milk and water.

And so, Michelle’s English literacy gains ground. We wait for an opportunity to infuse Russian and French. We know we need to proceed in ways appropriate for a five-year-old. “The most common mistake people make is to ask for too much too soon.” I came upon this recommendation once for training cats—but somehow it fits perfectly within any learning context! So we are patient, and we take small steps. The same source notes, “If a behavior results in something the [learner] likes, she will do it again.”

As grandparents, we are now planning for our next visit with Michelle and her brother Maxim. Here are a few thoughts on our next steps to support their engagement with literacy.

- Be ready with a few vocabulary games and activities. Reading can be a source of frustration when a text has too many unknown words.

- Create short, engaging stories together, modelling writing.

- Start a daily journal with the children.

- Write cards and letters to family and friends.

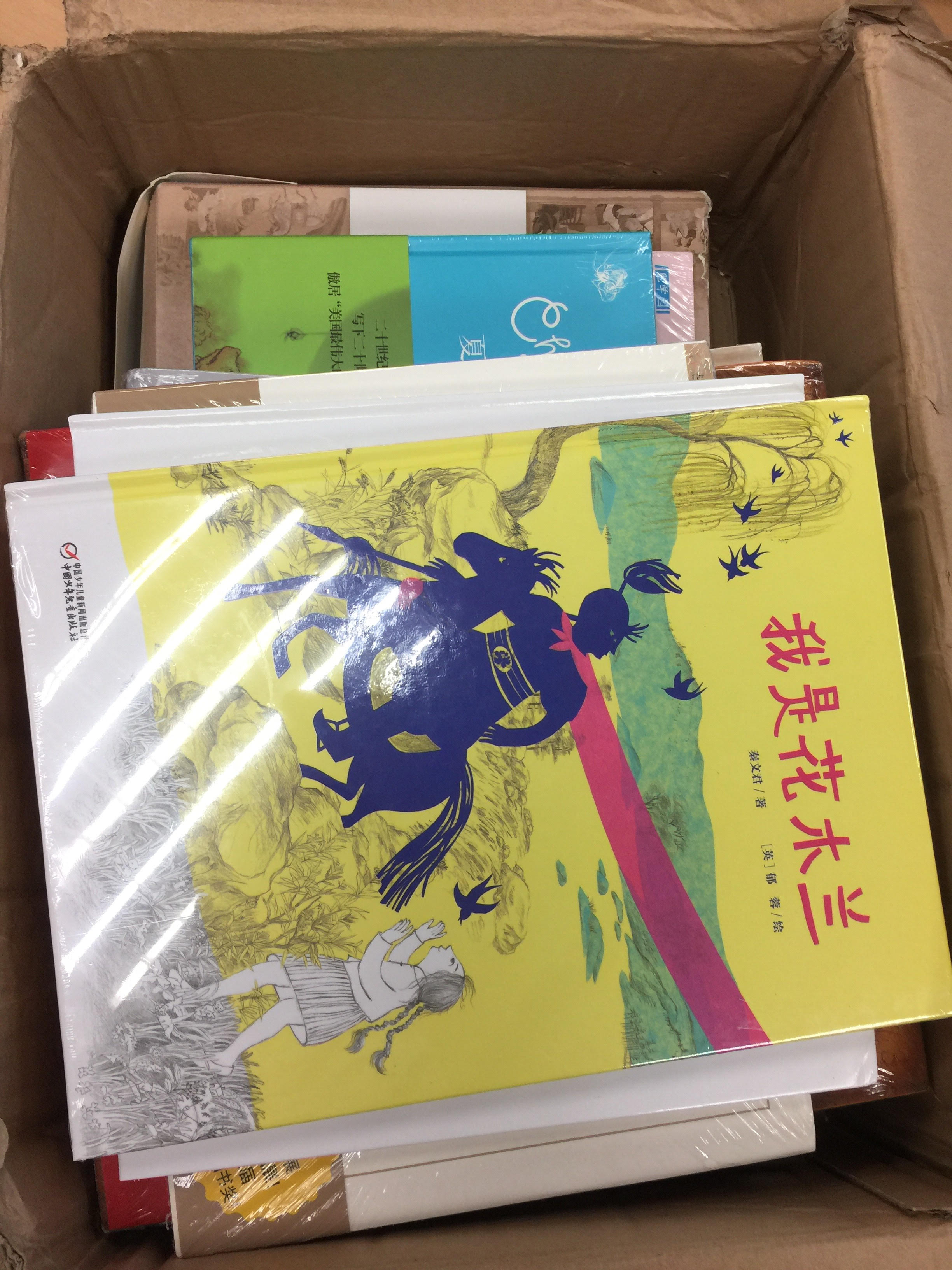

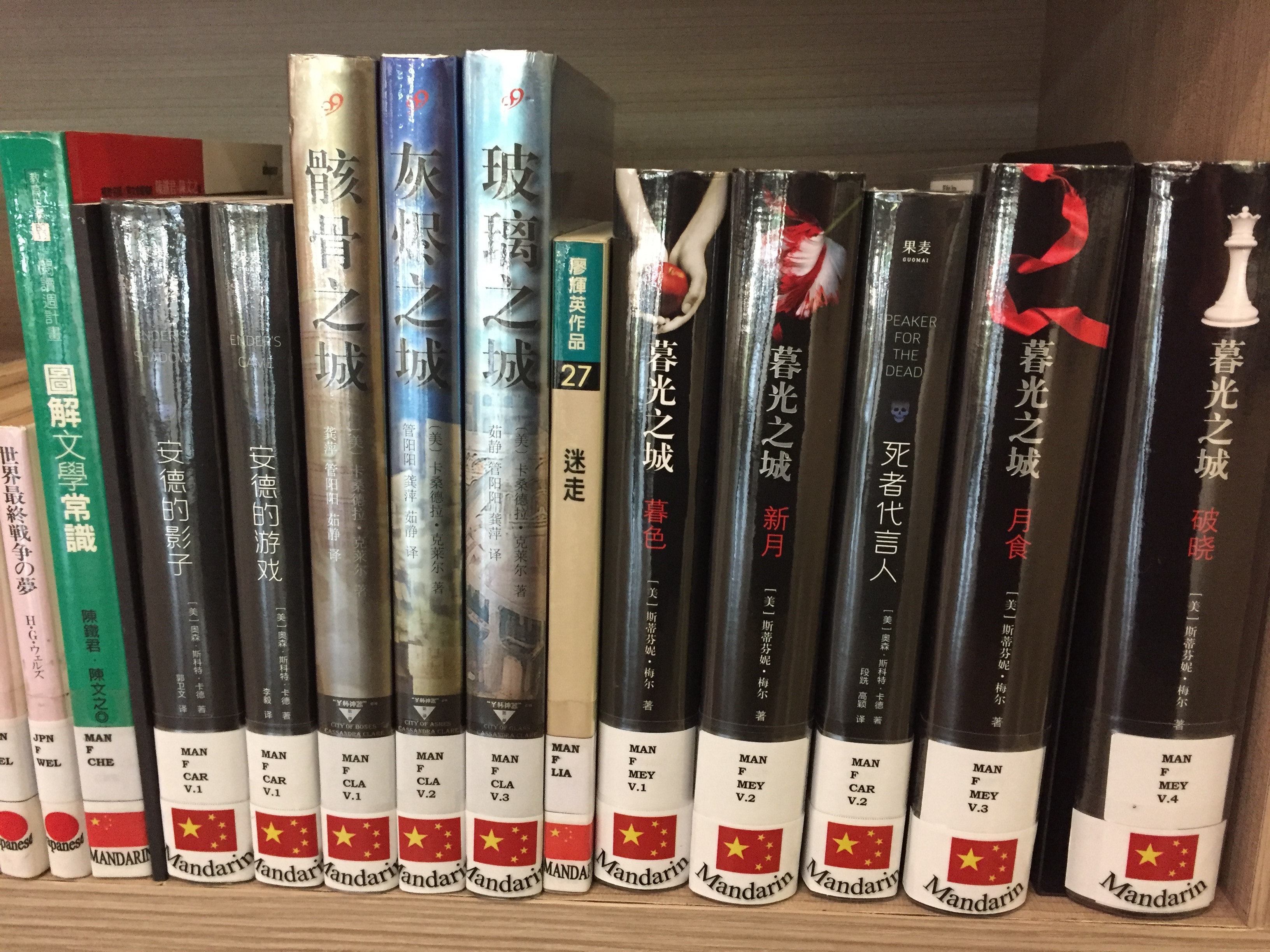

- Maintain a supply of books in their languages—books with simple text for independent reading, and books with more complex language for reading aloud to the children.

- Collect stamps, postcards, labels and other objects with print in their languages.

- Engage children in letter and word sorting games to differentiate different scripts—especially looking for letters that are “the same but different.”

- Create name cards in multiple languages.

- Have conversations about literacy.

Recommended reading:

Mother tongue: Why is it important for education?