A lot has been said here about balancing languages—and we have noted that much depends on our goals, needs, and available resources. Just as plants depend on the quality of soil and environment for their optimal growth, so children’s growth and linguistic development depend on the quality of their linguistic environment. When we put a plant on the balcony in a pot, we devise a plan for how to support its optimal growth in the given conditions. We provide fertilizers, protection from insects, and so on—a handbook on taking care of house plants gives many recipes. With children, when there is lack of certain ingredients for supporting native languages, we might turn to a manual on raising multilingual children, or design our own plan of support.

In this endeavor, we depend a lot on extra effort: our effort, and effort exerted by our children. “You have to make an effort and kick as hard as you can”—our four-year-old granddaughter Michelle recently realized for the first time, during swimming lessons, that learning requires effort. And resilience. No matter what you learn. In the end, effort and resilience bring reward and motivation.

Michelle is enjoying becoming trilingual. It feels very natural to her and appears effortless. Experience tells us, however, that a more rigorous and structured approach to mastering three languages will need to become part of the language plan. She will soon start school in English, which will set high expectations on her and will require continuous mastering of the language of instruction. This will pose additional challenges for maintaining her two home languages, Russian and French, and will certainly require extra effort and resilience.

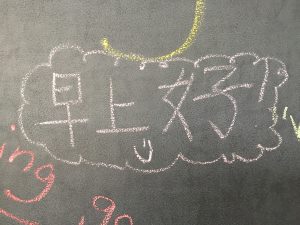

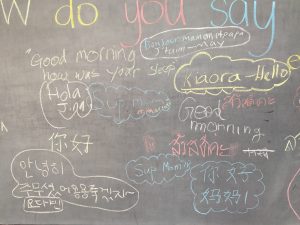

Parents and close family members become models at the early stages of language development. As children grow, the circle of available linguistic models becomes wider and includes playmates, peers, teachers and other members of the social and academic context. Languages used within these circles will constantly tip the balance in more than one direction and might cause losses in native languages used at home.

At the early stages, therefore, it is especially important to anticipate this happening and to be ready to provide motivation and support for keeping native languages functional. The ultimate responsibility for supporting home languages lies with the family. Our role as adults is to understand the importance of a combined effort—the effort and challenge that pushes the child to the necessary level of independence and linguistic flexibility.

To be able to support our children linguistically we also need to challenge ourselves and push our limits of linguistic knowledge and competence. The level of our mastery will be the foundation for our kids’ growth. Research shows that parental language input style and complexity predicts child language development.

What can we do to make sure we support and maintain our children’s multilingual proficiency in the years to come?

The first very important step is to continue being models for our children and maintain a relationship with them that goes deeper than meeting their basic needs. Children love to ask questions. As they grow older, their questions, thoughts, and opinions will become more sophisticated. We need to be prepared to have conversations with children on various topics; to keep them motivated by stimulating their interests and encouraging their curiosity; and to put them in situations requiring precise and complex language. Through all this, we are fostering their cultural and linguistic identities.

Here are some things we can do on a regular basis, in the languages we support, with enthusiasm, but also with effort and resilience:

Games

Many games involve functional use of language, requiring children to describe, give definitions, use complex vocabulary, ask questions, negotiate meaning, use various linguistic elements, and reinforce specific skills and competencies.

Activities

Many activities need specific language to accomplish them: role playing, storytelling, cooking, crafting, planting, tidying up, sewing, fixing, swimming, etc.

Social Events

Social events provide opportunities to participate in family gatherings and celebrations; connect with playmates; and talk with people of different ages, areas of expertise, and personalities. These events provide exposure to cultural norms and ways of discourse, promoting understanding and acceptance of behaviors and ways of thinking and talking.

Collecting Knowledge and Experiences

Trips to new places and visits to theatres, museums, lectures and workshops encourage curiosity, build foundations for cultural and scientific literacy, and enrich language.

Literacy

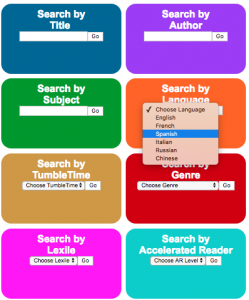

Literacy activities are building blocks of cognitive and emotional development. Look for books that have rich language and offer a high level of interest as well as challenge. Read to and with children; have conversations and discussions around texts; engage in retelling and interpretations. Literacy activities also include writing letters to relatives and friends, and keeping journals.

Columnist Olga Steklova is a retired EAL teacher at ISB and trilingual herself. She shares tips for raising multilingual children as she observes her own grandchildren. To read more columns, click on the Ask Olga! category below.