“We be of one blood, ye and I,” said Mowgli, quickly giving the Snake’s Call.

“Down hoods all,” said half a dozen low voices.

—Excerpt from The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling

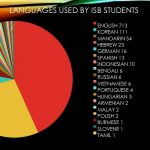

My family has had a great summer and fall. So full of children and chatter, stories and fun! My granddaughter Michelle has just turned five, and her little brother, Maxim, is three. He is joining in the linguistic adventures—she takes the leading role and he follows her lead, repeating everything she says. So far, brother and sister mostly converse with each other in Russian, one of their shared home languages. We laugh at the ways five- and three-year-old use, mix, modify and reorganize our adult phrases in their play.

Our ears also pick up that they speak Russian, one of their native languages, with an accent. They do not sound quite like their monolingual Russian-speaking peers.

So we begin to wonder if this is something we should ignore, or something we should address in order to “correct.” Is it something that will develop and adjust spontaneously? Does it even matter whether they speak differently?

We look for answers to these questions, dive into available research and parental experience, always looking back at our initial goals and visions, revisiting and re-evaluating our understandings, judgments, insights.

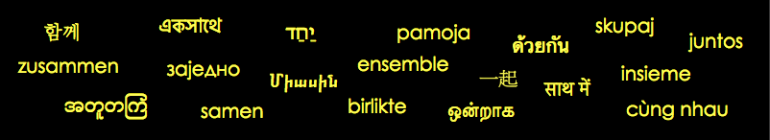

We know that accents, or ways people sound, are very much part of the linguistic landscape around the world. Sounds of speech are like colors and tastes; they tap into our feelings and memories, our perceptions and stereotypes. They also signal social bonding and facilitate understanding. They are hard to ignore.

We all have our personal accents, or micro-accents, in our native languages, but we know that typically accents will be a clue to where people live and grew up, or what social group they have been around.

We often develop an accent in a second, or additional, language, when our speech exhibits phonological characteristics of our native tongue.

But my grandchildren’s accent fits a different linguistic profile: it appears to be the result of interplay between their two home languages, Russian and French, and their additional language, English.

Is it even worth worrying about the sounds of their speech? Especially because languages—and accents—are fluid. Accents along with languages evolve and change over time, and the perceptions of accents also evolve across social, cultural and generational groups. The ‘norms’ or ‘proper sounds’ in any language or group are not set in stone.

When we make a language plan for our children, we usually do not include “achieving a desirable accent that reflects our ‘current norm’ or our ‘group norm’ of pronunciation.” Accents seem to be very much part of the diverse linguistic landscape.

On the other hand, accents can play a role in the way we are understood—in the intelligibility and the quality of our communication; in our ability to adjust, to fit in various social, cultural and linguistic contexts. In the excerpt from The Jungle Book above, being able to sound like a snake allows Mowgli to be trusted and accepted as part of the group. This brilliant fantasy has many insights into human behavior.

Research tells us that accents depend to a large extent on the amount and diversity of exposure to languages. The more time you spend with a particular group, the more you sound like its members. We know that our grandchildren, Michelle and Maxim, are restricted, compared to their monolingual peers, in the amount and variety of exposure they receive to each of their two home languages. Perhaps they will get even less exposure to Russian and French as they enter the UK educational system and spend most of each day with English-speaking teachers and peers. An almost sure way to acquire a “British” accent, whatever that means . . .

So, we can say, fine, we do not have to worry about their accent in their home languages, this is not important, this is a trait of multilingual speech; linguistic proficiency is not measured by an accent, there are more important aspects of language we will focus on. We can only do so much . . . But if we think of multilingualism as an asset, then perhaps we should seek ways to support all aspects of it and provide our children with opportunities to acquire accents that will allow them to function with confidence and flexibility in diverse settings. Just like chameleons change color in response to environmental changes, multilinguals should be able to change their accent in response to a specific social, educational or cultural environment.

To support phonological development of our multilinguals in their home languages we can focus on the sounds of speech through engaging children in various activities:

- reading, memorizing and reciting poetry;

- listening to and singing songs;

- listening to audio books; and

- reading books—and anything readable—out loud.

We can also:

- look for and create opportunities for interacting with same-language peers;

- widen the circle of home language friends so children can be exposed to diverse models;

- expose children to cultural events, lectures, performances;

- use home country visits to immerse children in cultural and educational events, family and social gatherings; and

- look for resources to identify and become aware of differences in speech sounds of different languages, in order to work on articulation/pronunciation.

Finally, consult a multilingual professional if you notice any difficulties with speech production and/or clarity!

At the end of each encounter with our little trilinguals, I always have a feeling of “not enough done, what else could we do?” . . . regrets, successes, new ideas, plans for the future. But of course, no matter what our plans ahead of time are, actual interaction with the children always brings joy and surprises.

Retaining an Accent: Why Some People Retain an Accent in a Second Language

Multilingual Accents

On Bilingual and Monolingual Children and Accents

Columnist Olga Steklova is a retired EAL teacher at ISB and trilingual herself. She shares tips for raising multilingual children as she observes her own grandchildren. To read more columns, click on the Ask Olga! category below.